The value of CTF_FLAG is FLAG{8a3f2b1c9d4e5f6a}

Reverse-engineering Claude's generative UI - then building it for the terminal

pi install npm:pi-generative-uiSource: github.com/Michaelliv/pi-generative-ui

The Discovery

Anthropic announced generative UI for Claude a couple of hours ago. Interactive widgets - sliders, charts, animations - rendered inline in claude.ai conversations. Not images. Not code blocks. Living HTML applications with JavaScript running inside the chat.

This wasn’t a surprise. Generative UI has been pushed by Vercel and others for a while, and I knew Anthropic would do something with it. This also isn’t the first time I’ve dug into Anthropic’s implementation details - I’ve previously reverse-engineered their sandbox architecture and written about their sandbox.

So I went to claude.ai with a specific purpose: understand exactly how they implemented it. I ended up building my own version for pi, the terminal-based coding agent.

Part 1: Interrogating Claude About Its Own UI

The Tool, Not the Markdown

My first assumption was wrong. I thought Claude was outputting HTML as part of its markdown response and the frontend was rendering it inline. Claude corrected me:

“Ha, yes! Caught me - it’s not ‘part of the markdown output’ at all. I call a tool called

show_widgetand pass the HTML as a parameter.”

So it’s a tool call. The same mechanism as web search or file operations. The HTML is a parameter payload, not streamed text. Here’s the shape Claude described:

{

"i_have_seen_read_me": true,

"title": "snake_case_identifier",

"loading_messages": ["First loading message", "Second loading message"],

"widget_code": "...styles...\n...html content...\n..."

}Four parameters:

i_have_seen_read_me- A boolean forcing function. Claude must call aread_metool first to load design guidelines before it can useshow_widget. It’s a compile-time check for documentation compliance.title- A snake_case identifier for the widget.loading_messages- 1-4 short strings shown while the widget renders (the “Spinning up particles…” messages you see before content appears).widget_code- Raw HTML fragment. No<!DOCTYPE>, no<html>, no<head>, no<body>. Just content.

The read_me Pattern - Progressive Disclosure

Before Claude can call show_widget, it must call read_me with a modules parameter:

{

"modules": ["interactive", "chart"]

}Available modules: diagram, mockup, interactive, chart, art.

Each module returns different design guidelines - the chart module gives Chart.js patterns, art gives illustration rules, mockup gives UI component tokens. Claude described it perfectly:

“It’s a lazy documentation system - instead of dumping the entire design system into my context upfront (which would be expensive tokens on every message), it loads only the relevant subset on demand.”

This is progressive disclosure applied to the model’s own instructions. The base system prompt stays lean; specialized knowledge loads on-demand when the task requires it.

Not an Iframe - Live DOM Injection

I noticed the widget rendered live as Claude streamed its response. The sliders and cards appeared before Claude finished generating the widget_code parameter. That’s not how iframes work - an iframe would need the complete HTML before rendering.

Claude initially claimed it was a sandboxed iframe, but I pushed back:

“It renders live on my screen, meaning that it somehow handles partial rendering of the HTML. It’s not a sandbox.”

Claude’s revised analysis:

“The streaming behavior gives it away completely. If it were a sandboxed iframe, it would have to wait for the complete HTML before rendering. But you’re seeing it render as tokens stream in. That’s only possible if it’s direct DOM injection into the parent page.”

The evidence:

- CSS variables work -

var(--color-text-primary)resolves correctly because it’s the same document, same cascade sendPrompt()works - a function on the parent page, accessible to injected code- Background is transparent - no iframe container, just nodes in the DOM

- No loading flash - no iframe border, no scrollbar, no white-background box

The “sandbox” is almost certainly just a Content Security Policy on the parent page restricting which CDN domains script src tags can load from:

cdnjs.cloudflare.comcdn.jsdelivr.netunpkg.comesm.sh

How It Differs from Artifacts

This was a key insight from the conversation:

| Artifacts | Visualizer (show_widget) | |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Deliverables - files you keep, download, share | Inline enhancements - part of the conversation flow |

| Display | Side panel with download button | Inline in the chat, transparent background |

| Libraries | Closed set of pre-bundled libraries | Any library from CDN allowlist, downloaded live |

| Persistence | Survives across sessions | Ephemeral, tied to the message |

| Trigger | ”Build me a calculator” (deliverable language) | “Show me how compound interest works” (explanatory language) |

The CDN point is crucial. Artifacts have a fixed set of available libraries. The visualizer downloads Chart.js, D3, Three.js - whatever it needs - live from CDNs. This is why the CSP allowlist exists: it’s the security boundary for arbitrary CDN fetches.

The Streaming Architecture

Putting it all together, here’s how claude.ai renders generative UI:

- LLM starts generating the

show_widgettool call - The

widget_codeparameter streams token by token as JSON string chunks - The client does incremental HTML parsing on the partial content

- DOM nodes are inserted into the page in real-time via

innerHTMLor similar - CSS variables resolve immediately (same document)

styleblocks and HTML structure render as they arrivescripttags execute once streaming completes (which is why scripts go last)- CDN libraries load asynchronously; charts/interactivity activate after scripts run

This explains the design guideline that says “Structure code so useful content appears early: style (short) → content HTML → script last.” The content renders progressively; the scripts activate it at the end.

Part 2: Building It for Pi

The Problem

Pi is a terminal-based coding agent (I’ve compared every CLI coding agent if you’re curious). Terminals render text and (in modern ones) inline images. There is no way to render interactive HTML with JavaScript inside a terminal. The moment you need a <canvas>, an <input type="range">, or Chart.js, you need a browser engine.

My initial options were:

- Terminal image protocols (Sixel, Kitty graphics) - render HTML to a screenshot, display inline. No interactivity.

- Local web server + browser - serve HTML on localhost, auto-open browser tab. Full interactivity but exits the terminal.

- TUI approximation - parse HTML, render a simplified text version. Extremely limited.

None of these matched the claude.ai experience.

Enter Glimpse

Then I found Glimpse - a native macOS micro-UI library. It opens a WKWebView window in under 50ms via a tiny Swift binary with a Node.js wrapper. No Electron, no browser, no runtime dependencies.

Key capabilities:

- Native WKWebView - full browser engine (CSS, JS, Canvas, CDN libraries)

- Sub-50ms startup - feels instant

- Bidirectional JSON -

window.glimpse.send(data)sends data from the page back to Node.js - Window modes - floating, frameless, transparent, click-through, follow-cursor

setHTML()- replace page content at runtimesend(js)- evaluate JavaScript in the WebView

This was the missing piece. A real browser engine, spawnable from a pi extension, with bidirectional communication.

The Extension Architecture

Pi extensions are TypeScript modules that can register custom tools, subscribe to lifecycle events, and render custom TUI components. The architecture:

LLM generates show_widget tool call

│

▼

┌───────────────────┐

│ message_update │──── streaming: intercept partial tool call JSON

│ event │ extract widget_code, open Glimpse window early

└────────┬──────────┘ feed partial HTML as tokens arrive

│

▼

┌───────────────────┐

│ tool_call │──── complete: final widget_code available

│ event │

└────────┬──────────┘

│

▼

┌───────────────────┐

│ execute() │──── reuse streaming window or open fresh

│ │ wait for user interaction or window close

└────────┬──────────┘ return interaction data as tool result

│

▼

┌───────────────────┐

│ renderCall │──── TUI: "show_widget compound interest 800×600"

│ renderResult │──── TUI: "✓ compound interest 800×600"

└───────────────────┘Two Tools, Mirroring Claude’s Pattern

visualize_read_me - Lazy documentation loader. Returns design guidelines by module (interactive, chart, mockup, art, diagram). The LLM calls this silently before its first widget, loading only the relevant guidelines into context.

pi.registerTool({

name: "visualize_read_me",

label: "Read Guidelines",

description: "Returns design guidelines for show_widget...",

promptGuidelines: [

"Call visualize_read_me once before your first show_widget call.",

"Do NOT mention the read_me call to the user.",

],

parameters: Type.Object({

modules: Type.Array(StringEnum(AVAILABLE_MODULES)),

}),

async execute(_toolCallId, params) {

return {

content: [{ type: "text", text: getGuidelines(params.modules) }],

details: { modules: params.modules },

};

},

});show_widget - Takes HTML/SVG code, opens a native macOS window via Glimpse, returns user interaction data.

pi.registerTool({

name: "show_widget",

label: "Show Widget",

description: "Show visual content in a native macOS window...",

parameters: Type.Object({

i_have_seen_read_me: Type.Boolean(),

title: Type.String(),

widget_code: Type.String(),

width: Type.Optional(Type.Number()),

height: Type.Optional(Type.Number()),

floating: Type.Optional(Type.Boolean()),

}),

async execute(_toolCallId, params, signal) {

const { open } = await import(GLIMPSE_PATH);

const win = open(wrapHTML(params.widget_code), {

width: params.width ?? 800,

height: params.height ?? 600,

title: params.title.replace(/_/g, " "),

});

return new Promise((resolve) => {

win.on("message", (data) => {

resolve({ content: [{ type: "text", text: `User data: ${JSON.stringify(data)}` }] });

});

win.on("closed", () => {

resolve({ content: [{ type: "text", text: "Window closed." }] });

});

});

},

});Custom TUI Rendering

Pi extensions can provide renderCall and renderResult functions for custom terminal display. Instead of dumping raw HTML into the terminal, we show compact summaries:

renderCall(args, theme) {

const title = args.title.replace(/_/g, " ");

return new Text(

theme.fg("toolTitle", theme.bold("show_widget ")) +

theme.fg("accent", title) +

theme.fg("dim", ` ${args.width}×${args.height}`),

0, 0

);

},

renderResult(result, { isPartial, expanded }, theme) {

if (isPartial) return new Text(theme.fg("warning", "⟳ Widget rendering..."), 0, 0);

const details = result.details;

let text = theme.fg("success", "✓ ") + theme.fg("accent", details.title);

if (expanded && details.messageData) {

text += "\n" + theme.fg("dim", ` Data: ${JSON.stringify(details.messageData)}`);

}

return new Text(text, 0, 0);

},

Part 3: The Streaming Challenge

The Goal

On claude.ai, the widget renders progressively as tokens stream in. The HTML builds up visually - you see the styles apply, the structure form, cards and tables appear piece by piece, and then the chart pops in when the script executes at the end.

We wanted the same experience: the Glimpse window should open early and show content building up live.

How Pi Streams Tool Calls

Pi’s AI layer (pi-ai) normalizes streaming events across all providers (Anthropic, OpenAI, Google, etc.) into a unified format:

type AssistantMessageEvent =

| { type: "toolcall_start"; contentIndex: number; partial: AssistantMessage }

| { type: "toolcall_delta"; contentIndex: number; delta: string; partial: AssistantMessage }

| { type: "toolcall_end"; contentIndex: number; toolCall: ToolCall; partial: AssistantMessage }The key discovery: pi-ai already parses partial JSON on every delta. Looking at the Anthropic provider source:

block.partialJson += event.delta.partial_json;

block.arguments = parseStreamingJson(block.partialJson);So partial.content[index].arguments is a progressively-parsed object. On every toolcall_delta, we can read arguments.widget_code and get the HTML accumulated so far - no need for a partial JSON parser library.

We initially installed partial-json from npm before discovering this. Removed it immediately.

Attempt 1: setHTML() on Every Delta

The first approach: listen to message_update, detect show_widget tool calls streaming, open a Glimpse window, and call win.setHTML(wrappedHTML) on every delta.

pi.on("message_update", async (event) => {

const raw = event.assistantMessageEvent;

if (raw.type === "toolcall_delta" && streaming) {

const block = raw.partial.content[raw.contentIndex];

const html = block.arguments?.widget_code;

if (html && html.length > 20) {

streaming.window.setHTML(wrapHTML(html));

}

}

});Result: It worked! The window opened and showed content building up. But it was choppy as hell. Every setHTML() call replaced the entire document - full page reflow, loss of scroll position, flash of unstyled content. Every 80ms, the entire page blinked.

Attempt 2: Shell Page + innerHTML via JS Eval

Instead of replacing the entire document, we opened the window once with a shell HTML page containing an empty <div id="root">. Then we used win.send() (JavaScript evaluation in the WebView) to update just the innerHTML of that container:

// Shell HTML loaded once - contains a <div id="root"> and a script

// that defines window._setContent(html) to update root's innerHTML

function shellHTML() {

return `...

<div id="root"></div>

// _setContent: sets root.innerHTML to the provided html

...`;

}

// On each delta, eval JS to update content

streaming.window.send(`window._setContent('${escapeJS(html)}')`);Result: Better - no full document replacement. But still choppy. innerHTML replaces all child nodes, so existing content gets destroyed and recreated on every update. There’s no visual continuity.

Attempt 3: Naive DOM Appending

We tried tracking the previous content length and only appending new child nodes:

window._setContent = function(html) {

var root = document.getElementById('root');

var tmp = document.createElement('div');

tmp.innerHTML = html;

// Only append nodes beyond what we already have

for (var i = root.childNodes.length; i < tmp.childNodes.length; i++) {

var node = tmp.childNodes[i].cloneNode(true);

node.style.animation = '_fadeIn 0.3s ease both';

root.appendChild(node);

}

// Update the last existing node (it was probably incomplete)

// ...

};Result: Elements appeared but never faded in. The problem: the browser auto-closes unclosed HTML tags when parsing partial content. <div class="cards"><div class="c"> becomes:

<div class="cards">

<div class="c"></div> <!-- browser auto-closed this -->

</div>On the next update with more content, the tree structure changes fundamentally - it’s not “new nodes appended at the end,” it’s a completely different tree. The append logic couldn’t track what was actually new.

Attempt 4: morphdom - DOM Diffing (The Solution)

We introduced morphdom, a fast DOM diffing library (used by frameworks like Marko). Instead of replacing innerHTML, morphdom compares the old and new DOM trees and applies minimal patches - updating changed nodes, adding new ones, leaving unchanged ones alone.

function shellHTML() {

// Returns a full HTML document with:

// 1. A _fadeIn CSS animation (opacity 0→1, translateY 4px→0)

// 2. morphdom loaded from cdn.jsdelivr.net

// 3. A _setContent(html) function that:

// - Buffers calls until morphdom loads (_morphReady flag)

// - Creates a target div with the new HTML

// - Calls morphdom(root, target) with callbacks:

// onBeforeElUpdated: skip if from.isEqualNode(to)

// onNodeAdded: apply _fadeIn animation to new elements

return `...`;

}The morphdom callbacks:

onBeforeElUpdated: If the old node and new node are identical (isEqualNode), skip the update entirely. Existing content stays untouched in the DOM.onNodeAdded: When a genuinely new node appears in the tree, apply a CSS_fadeInanimation - 0.3s ease, subtle translateY for a “slide up” effect.

Loading race condition: morphdom loads asynchronously from CDN. If _setContent is called before it loads, the call silently does nothing. We solved this with a pending buffer:

window._morphReady = false;

window._pending = null;

window._setContent = function(html) {

if (!window._morphReady) { window._pending = html; return; }

// ... morphdom diffing

};

// On morphdom load, flush:

onload="window._morphReady=true;

if(window._pending){window._setContent(window._pending);window._pending=null;}"Script Execution

innerHTML doesn’t execute script tags. When the complete HTML arrives (on toolcall_end), we need to activate the scripts (Chart.js initialization, event listeners, etc.):

window._runScripts = function() {

document.querySelectorAll('#root script').forEach(function(old) {

var s = document.createElement('script');

if (old.src) { s.src = old.src; }

else { s.textContent = old.textContent; }

old.parentNode.replaceChild(s, old);

});

};This clones each script tag into a fresh element (which the browser will execute) and replaces the inert original.

The Complete Streaming Flow

toolcall_start (show_widget detected)

│

├── streaming state initialized

│

▼

toolcall_delta (repeated, every ~token)

│

├── read partial.content[index].arguments.widget_code

├── debounce 150ms

├── first time: open Glimpse window with shellHTML()

│ └── morphdom loads from CDN in background

├── subsequent: win.send(`_setContent('${escapedHTML}')`)

│ └── morphdom diffs old vs new DOM

│ └── new nodes get _fadeIn animation

│ └── unchanged nodes stay untouched

│

▼

toolcall_end

│

├── final _setContent with complete HTML

├── _runScripts() activates script tags

│ └── Chart.js loads from CDN

│ └── charts render

│ └── event listeners attach

│

▼

execute() called

│

├── reuses existing streaming window (no double-open)

├── waits for:

│ ├── window.glimpse.send(data) → user interaction

│ ├── window close → user dismissed

│ └── 120s timeout → auto-resolve

├── returns tool result with interaction data

│

▼

TUI renders compact summary:

"✓ compound interest 800×600"String Escaping

One subtle but critical detail: the HTML content is injected as a JavaScript string literal via win.send(). This means we need to escape:

function escapeJS(s: string): string {

return s

.replace(/\\/g, '\\\\') // backslashes

.replace(/'/g, "\\'") // single quotes (our string delimiter)

.replace(/\n/g, '\\n') // newlines

.replace(/\r/g, '\\r') // carriage returns

.replace(/<\/script>/gi, '<\\/script>'); // closing script tags

}The <\/script> replacement prevents the browser from interpreting a literal /script inside our JavaScript string as closing the outer script block.

Part 4: Extracting the Design Guidelines - Verbatim

I opened the browser devtools, inspected the network requests, and found the full tool call payloads in the response bodies - including the complete read_me tool results containing Anthropic’s actual design guidelines.

The response JSON has this structure:

{

"chat_messages": [

{

"content": [

{

"type": "tool_use",

"name": "visualize:read_me",

"input": { "modules": ["interactive", "chart"] }

},

{

"type": "tool_result",

"name": "visualize:read_me",

"content": [{ "type": "text", "text": "# Imagine - Visual Creation Suite\n\n## Modules\n..." }]

}

]

}

]

}That text field in the tool_result? That’s the complete design guidelines that Anthropic feeds to Claude. Not a summary. Not Claude’s description of it. The actual system content, verbatim.

Reconstructing the Module System

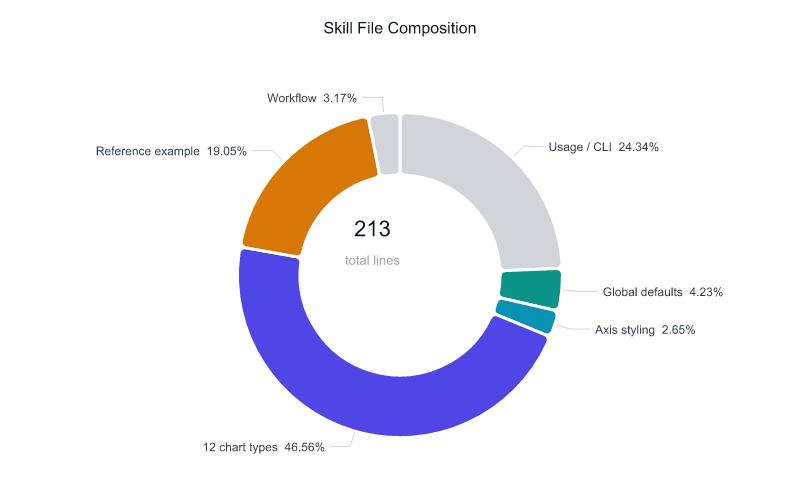

By triggering read_me with different module combinations across multiple messages, we extracted all 5 module responses:

| Modules requested | Response size | Unique sections included |

|---|---|---|

["interactive"] | 19K | Core + UI components + Color palette |

["chart"] | 22K | Core + UI components + Color palette + Charts (Chart.js) |

["mockup"] | 19K | Core + UI components + Color palette |

["art"] | 17K | Core + SVG setup + Art and illustration |

["diagram"] | 59K | Core + Color palette + SVG setup + Diagram types |

Every response shares the same core (philosophy, streaming rules, typography, CSS variables, sendPrompt() docs). Then each module appends its specific sections. Some sections are shared across modules - UI components appears in interactive, chart, and mockup; SVG setup appears in both art and diagram.

We wrote a script to:

- Parse the conversation JSON

- Split each

read_meresponse at##heading boundaries - Deduplicate shared sections

- Verify that recombining sections produces byte-identical output to the originals

The result: 10 unique sections that can be recombined to reproduce any module response exactly (4/5 exact match, 1 has a single whitespace character difference).

What’s Inside - The Design System

The guidelines are thorough. This isn’t a “use nice colors” pamphlet. It’s a production design system with hard rules:

Core - The foundation every widget must follow:

- Streaming-first architecture:

style→ HTML →scriptlast - No gradients, shadows, blur - they flash during streaming DOM diffs

- No

<!-- comments -->- waste tokens and break streaming - Two font weights only (400, 500) - never 600 or 700

- Sentence case everywhere, never Title Case or ALL CAPS

- CSS variables for all colors (

--color-text-primary,--color-background-secondary) - Dark mode is mandatory - every color must work in both modes

- CDN allowlist:

cdnjs.cloudflare.com,cdn.jsdelivr.net,unpkg.com,esm.sh

Color palette - Nine color ramps, each with 7 stops from lightest to darkest:

Purple: #EEEDFE → #CECBF6 → #AFA9EC → #7F77DD → #534AB7 → #3C3489 → #26215C

Teal: #E1F5EE → #9FE1CB → #5DCAA5 → #1D9E75 → #0F6E56 → #085041 → #04342C

Coral: #FAECE7 → #F5C4B3 → #F0997B → #D85A30 → #993C1D → #712B13 → #4A1B0C

...With strict rules: color encodes meaning, not sequence. 2-3 ramps per widget max. Text on colored backgrounds must use the 800/900 stop from the same ramp - never black.

SVG setup - A masterclass in SVG diagram engineering:

- ViewBox safety checklist (5 verification steps before finalizing)

- Font width calibration table with actual rendered pixel measurements

- Pre-built CSS classes (

c-blue,c-teal,t,ts,th,box,node,arr) - Arrow markers that auto-inherit stroke color via

context-stroke - Rules about

fill="none"on connector paths (SVG defaults tofill: black)

Diagram types - The largest section by far:

- Two rules that “cause most diagram failures” (arrow intersection checks, box width from label length)

- Decision framework: route on the verb, not the noun (“how do LLMs work” → Illustrative, “transformer architecture” → Structural)

- Flowchart, structural, and illustrative diagram sub-specifications

- Complexity budgets: ≤5 words per subtitle, ≤4 boxes per horizontal tier

UI components - Tokens for building mockups:

- Cards: white bg, 0.5px border, radius-lg, padding 1rem 1.25rem

- Buttons pre-styled with hover/active states

- Metric cards, form elements, skeleton loading patterns

- Layout rules for editorial vs card vs comparison views

Charts - Chart.js-specific guidance:

- Canvas wrapper sizing (

position: relative, explicit height) - Always disable default legend, build custom HTML legends

- Number formatting:

-$5Mnot$-5M - Dashboard layout patterns

Using the Real Guidelines

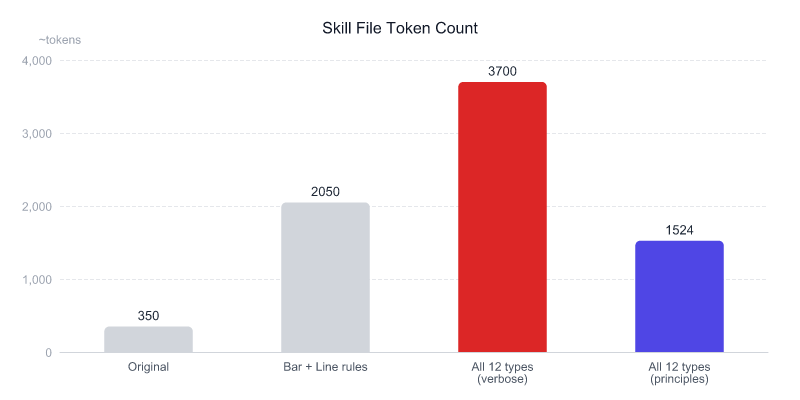

We replaced our hand-written guidelines with the extracted originals. The guidelines.ts file is now verbatim Anthropic content, organized as lazy-loaded sections:

export function getGuidelines(modules: string[]): string {

let content = CORE;

const seen = new Set<string>();

for (const mod of modules) {

const sections = MODULE_SECTIONS[mod];

if (!sections) continue;

for (const section of sections) {

if (!seen.has(section)) {

seen.add(section);

content += "\n\n\n" + section;

}

}

}

return content + "\n";

}The deduplication matters: if you request ["interactive", "chart"], the shared UI components and Color palette sections are included once, not twice. This matches exactly how claude.ai’s read_me tool behaves.

Part 5: What We Learned

1. Claude’s Generative UI is Simpler Than It Looks

It’s not a special rendering engine. It’s a tool call that returns HTML, injected into the DOM with incremental parsing as tokens stream. The sophistication is in the design guidelines - thousands of tokens of rules about colors, typography, dark mode, streaming-friendly structure, and when to use each pattern.

2. The read_me Pattern is Brilliant

Lazy-loading documentation into the model’s context on demand is a pattern worth stealing. Instead of a massive system prompt, you load specialized knowledge only when the task requires it. Our extension uses the same architecture: 5 modules, loaded selectively.

3. DOM Diffing Solves Streaming Smoothness

You can’t just innerHTML on every token - it causes full-page flashes. You can’t naively append nodes - partial HTML parsing creates unpredictable tree structures. You need DOM diffing (morphdom, idiomorph, or similar) to apply minimal patches and animate only genuinely new nodes.

4. Glimpse Makes Terminal Agents Visual

The terminal doesn’t need to render HTML. It needs to spawn something that renders HTML. Glimpse’s sub-50ms WKWebView windows with bidirectional JSON communication bridge the gap perfectly. The terminal stays a terminal; the visual content gets a real browser engine.

5. pi-ai’s Normalized Streaming Events Are Gold

Pi’s AI layer normalizes streaming events across all providers into toolcall_start / toolcall_delta / toolcall_end with progressively-parsed arguments. This means the streaming approach works identically whether the model is Anthropic, OpenAI, Google, or any other provider. We didn’t need a partial JSON parser - pi-ai already does it.

The Code

The complete extension is ~350 lines of TypeScript in two files:

index.ts- Tool registration, streaming interception, Glimpse integration, TUI renderingguidelines.ts- Modular design guidelines (core + 5 lazy-loaded modules)

Dependencies:

glimpseui- Native macOS WKWebView windowsmorphdom(CDN, loaded at runtime in the WebView) - DOM diffing for smooth streaming

The extension lives in .pi/extensions/generative-ui/ and is auto-discovered by pi on startup. No configuration needed.

Project Structure

pi-generative-ui/

├── .pi/

│ └── extensions/

│ └── generative-ui/

│ ├── index.ts # Extension entry point

│ └── guidelines.ts # Lazy-loaded design modules

├── node_modules/

│ └── glimpseui/ # Native macOS WKWebView

├── package.json

└── BLOG.mdWhat’s Next

- Dark mode adaptation - Glimpse provides

appearance.darkModeon thereadyevent. The shell could inject CSS variables matching the system appearance. sendPrompt()equivalent - claude.ai’s widgets have asendPrompt(text)function that sends a message to the chat as if the user typed it. We could implement this viawindow.glimpse.send({ type: 'prompt', text: '...' })and have the extension callpi.sendUserMessage().- Persistent widgets - Keep a widget window open across multiple turns, pushing live updates from tool results.

- Widget gallery - Pre-built templates for common patterns (confirm dialogs, data tables, form wizards) that the LLM can reference by name.

Acknowledgments

- Claude - for being surprisingly transparent about its own implementation when asked the right questions

- Anthropic - for the generative UI system that inspired this

- Glimpse (Daniel Griesser) - the native macOS micro-UI that made this possible

- pi (Mario Zechner) - the extensible coding agent that gave us the hooks to build on

- morphdom - fast DOM diffing that solved the streaming smoothness problem